The Elgin Cruck

John R Barrett - as published in the 2022 Moray Field Club Bulletin

Recent research into Anglo-Norman urban design (Barrett, 2019) highlighted the lack of determined archaeological excavation in Moray’s burghs: especially the very scanty nature of evidence for the built environment. A sketchy impression of domestic architecture in medieval towns is gained from the small corpus of Scottish urban archaeology (Bogdan, 1978; Holdsworth, 1987; Spearman, 1988; Bowler, 2004). In Moray, we must rely upon keyhole excavations (Hall, 1998, 2002), guesswork, inference and medieval burgh excavations in Inverness and Cromarty (Birch, 2017; Wordsworth, 1982). We can (tentatively) presume that the earliest burgh dwellings in Moray were timber-framed and stake-built, mud-and-dung-daubed, thatched halls. Evidence from Cromarty suggests that single-storeyed dwellings supported by earthfast posts were redeveloped as substantial timber-framed houses with stone foundations and (probably) jettied upper storeys. The evolution of domestic architecture tracks the growth of commercial prosperity and civic confidence – from the dependant burgess community of the twelfth century to the self-governing community that emerged during the fourteenth century.

Recent research into Anglo-Norman urban design (Barrett, 2019) highlighted the lack of determined archaeological excavation in Moray’s burghs: especially the very scanty nature of evidence for the built environment. A sketchy impression of domestic architecture in medieval towns is gained from the small corpus of Scottish urban archaeology (Bogdan, 1978; Holdsworth, 1987; Spearman, 1988; Bowler, 2004). In Moray, we must rely upon keyhole excavations (Hall, 1998, 2002), guesswork, inference and medieval burgh excavations in Inverness and Cromarty (Birch, 2017; Wordsworth, 1982). We can (tentatively) presume that the earliest burgh dwellings in Moray were timber-framed and stake-built, mud-and-dung-daubed, thatched halls. Evidence from Cromarty suggests that single-storeyed dwellings supported by earthfast posts were redeveloped as substantial timber-framed houses with stone foundations and (probably) jettied upper storeys. The evolution of domestic architecture tracks the growth of commercial prosperity and civic confidence – from the dependant burgess community of the twelfth century to the self-governing community that emerged during the fourteenth century.

Which brings us to the Elgin cruck. The feature was exposed during the building of the St Giles Centre in Elgin High Street. The discovery was photographed and reported; but it was not practicable at the time to take samples for radiocarbon dating or dendrochronology. And the timber was not preserved.

A cruck frame (couple) comprised a pair of arcing timbers jointed at the top, usually also with a transverse tie beam. A series of these A-frames supported the weight of a building’s roof, allowing the walls to be built of slighter timbers, or of turf, or of slighter timber framing infilled with stake-and-rice or wattle-and-daub panels. The cruck frames stood (perhaps on a stone pad) on the floor of the building within the walls, dividing the interior space into bays (each 6ft - 8ft in length). The width of a cruck-framed structure was limited by the size of available timbers. In burghs the width of a building was limited by the width of the burgage (25ft 6in), and the need for an access wynd (typically about 4ft wide). Cruck-framed buildings might be any length: large rural dwellings recorded in the eighteenth century extended to twelve bays, with the accommodation comprising a hall (firehouse),an unheated spence (bennerhouse), kitchen and chamber – probably also with lofts above formed by flooring supported on the cruck-frame tiebeams (Barrett, 2015, 55-60).

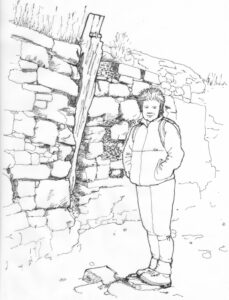

The Elgin cruck offers little evidence for the building it once supported. The cruck survives as a single blade of squared oak – measuring approximately 8in x 10in (20cm x 25cm) and 5ft 7in (1.7m) in length. It was a raised cruck – its foot planted on the lower courses of the wall. The cruck blade was embedded in a cruck-slot in the rubble wall. It would properly be described as a composite cruck: the top the timber was halved to form a joint with a (missing) upper section, and perhaps also with a tie beam. The joint was secured with a trenail – the wooden peg remaining in situ.

Piers Dixon (2002) suggested that earthfast posts gave way to cruck-framing (for rural buildings) in the fourteenth century; and so the rare Elgin cruck blade may be dated vaguely to some time between 1350 and the Great Rebuilding of the seventeenth century. Crucks leave little trace on the ground and, once removed, are invisible to archaeology. However, cruck framing is amply documented in archive sources (Mackay and Boyd, 1911, xcvi, 120, 186-7; Fenton and Walker, 1981, 44-56; Barrett, 2015). Doubtless, there are other early timbers embedded in the walls of later burgh buildings: waiting to be revealed during demolition and renovation; waiting to be recognised and recorded by alert antiquarians before they are ripped out and chucked in a skip.

References

- Barrett, J. R. (2015) The Making of a Scottish Landscape: Moray’s regular revolution, 1760 - 1840 (Fonthill, Croydon)

- Barrett, J. R. (2019) The Civilisation of Moray: burghs in the landscape and the landscape of burghs, c.1150 - c.1250 (MSc dissertation, University of Aberdeen)

- Birch, S. (2017) Cromarty Medieval Burgh Archaeology Project: Data Structure Report, 2015-16 (Cromarty)

- Bogdan, N. Q., and Wordsworth, J. W. (1978) Medieval Excavations in the High Street, Perth, 1975-76: an interim report (Perth)

- Bowler, D. P. (2004) Perth: the archaeology and development of a Scottish Burgh (Tayside & Fife Archaeological Committee, Perth)

- Dixon, P. (2002) ‘The medieval peasant building in Scotland: the beginning and end of the cruck’, in Ruralia, IV

- Fenton, A., and Walker, B. (1981) The Rural Architecture of Scotland (John Donald, Edinburgh)

- Hall, D. et al. (1998) ‘The archaeology of Elgin: excavations on Ladyhill and in the High Street, with an overview of the archaeology of the burgh’, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, volume 128 (Edinburgh)

- Hall, D. (2002) Burgess, Merchant and Priest: burgh life in the Scottish medieval town (Birlinn, Edinburgh)

- Holdsworth, P. (editor) (1987) Excavations in the medieval burgh of Perth, 1979 - 1981 (Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh)

- Mackay, W., and Boyd, H. C. (1911) Records of Inverness, volume 1, burgh court books, 1556-86 (Spalding Club, Aberdeen)

- Spearman, R. M. (1988) ‘The medieval townscape of Perth’, in M. Lynch et al., The Scottish Medieval Town (John Donald, Edinburgh)

- Wordsworth, J. (1982) ‘Excavations of the settlement at 13-21 Castle Street, Inverness, 1979’, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, volume 112 (Edinburgh)